Since the advent of the automobile, various individuals, companies and governments have sought to create “people’s cars”. Designed to make motoring accessible to the masses with affordability, durability and an appealing character, these cars are intended to be different from conventional vehicles.

In the 1980s, Canada’s Bombardier attempted to develop a modern version of a people’s car called the Venus – a small, Daihatsu-powered gem so cheap it could fit on a credit card. This could have been Canada’s answer to the iconic Beetle for modern times.

According to La Presse, it was in the early 1980s that Bombardier’s president, Laurent Beaudoin, made a trip to Paris and discovered a unique category of vehicle not yet seen in Canada. In Europe, there were quadricycles and “voitures sans permis” or “cars without a licence”.

Beaudoin was captivated by these charming vehicles and returned home determined to share his discovery with Yvon Lafortune, who was then managing Bombardier’s operations in Valcourt. As La Presse notes, Lafortune followed up on Beaudoin’s fascination by contacting the manufacturers of these tiny cars to explore the possibility of working together to bring their technology to Canada. However, they quickly learned that these microcars could not meet Canadian motor vehicle safety standards.

Undeterred, Bombardier forged ahead with its own compact car initiative. Rather than simply replicating European models, the company wanted to create an exceptionally affordable vehicle for the masses. It partnered with Daihatsu, a brand eager to enter the North American market.

In 1984, Bombardier’s vision was to develop most of the vehicle, with Daihatsu supplying a small engine and transmission. Lafortune assembled a team in a converted Bombardier family farm that had been turned into a design centre known as “the barn”.

This venture was called Project Venus, an acronym standing for Vehicle, Economical, New, Utilitarian and Safe. The Venus was envisioned with a groundbreaking design that was ahead of its time, while being priced under $5,000 (equivalent to about $11,724 today), making it accessible enough for a Canadian to purchase with a credit card.

At this stage, it’s important to remember that Bombardier had expertise in building ski-doos, motorcycles and trains, but lacked an automotive division. It was also two years before the company had acquired Canadair. The team assembled for the project was largely made up of people with no experience of automotive design and production.

One of the designers, Jean Labbé, had just graduated that year from the Art Center College of Design in Los Angeles and had no previous experience in the automotive industry. According to La Presse, he had to decide whether to start at the bottom at GM or take a chance on Bombardier’s ambitious project to design an entire car. At his side was Louis Morasse, another recent graduate with just six months’ industry experience from an internship at Peugeot. Morasse refined Labbé’s initial design and turned it into a presentation-ready prototype for Bombardier and Daihatsu.

In an interview with La Presse, Morasse highlighted the collaborative spirit of the Venus development process, noting that unlike traditional car manufacturers where designers compete, Bombardier’s recent graduates worked together towards a common goal.

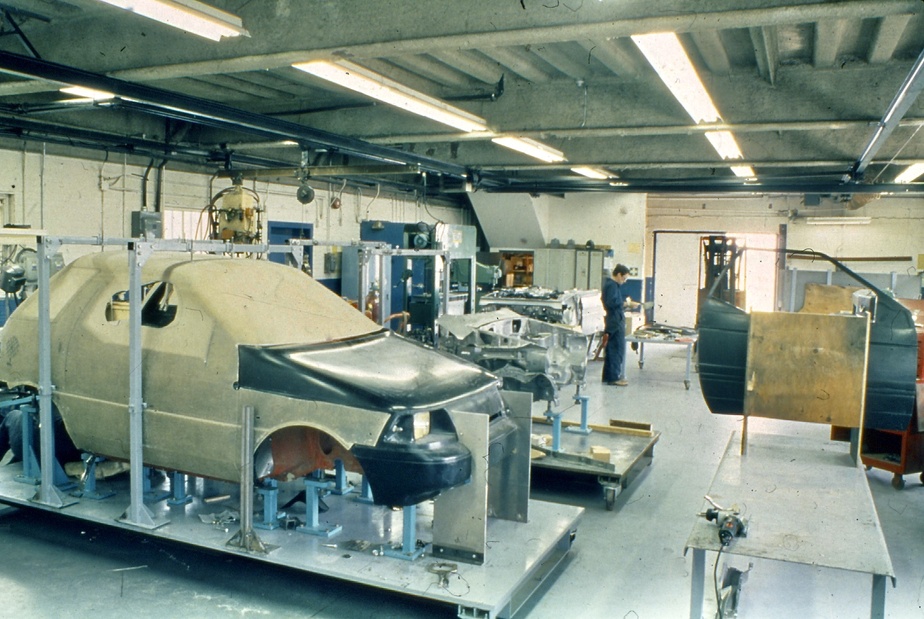

As the team moved forward, Bombardier was still in uncharted territory. They created a full-scale model using wood and putty, similar to the materials used for the Ski-Doo body, but this method had never been applied to something as large as an entire car. Although the Venus model was unexpectedly heavy, it effectively communicated their ideas.

The real challenge, as La Presse pointed out, was to turn the concept and mock-ups into a working vehicle. Yves Fontaine, the chief engineer for chassis and prototyping, had extensive experience of modifying rally cars, but had never built a production car. Essentially, a novice was at the helm, leading a team of newcomers. Despite this seemingly daunting mix, the team remained focused and completed a working prototype within six months. This prototype was a modified Japanese car that met the rough specifications of the Venus, and it performed well enough during testing at the Transport Canada facility to earn the praise of Daihatsu’s engineers.

As the project progressed, two more prototypes were developed, bringing the car closer to production. The next steps involved refining the design for production and establishing the necessary processes, including safety testing and parts design. Because Daihatsu’s engineers were unfamiliar with North American safety standards and the Canadian team had no experience with production vehicles, Bombardier sought the expertise of consultants based in Detroit.

The partnership with Daihatsu evolved into a more collaborative joint venture. The Charade and Rocky models, which Daihatsu intended to introduce to the North American market, were to be produced at Valcourt alongside the Venus.

However, a major challenge remained: how and where would these vehicles be sold and serviced? Bombardier, with its lack of automotive experience, didn’t have a dealer network. They did have an extensive network of Ski-Doo snowmobile dealers, but these were typically small, family-owned businesses in rural areas that were ill-suited to handle full automotive sales and service.

In response, Bombardier devised a plan to distribute the Venus through Canadian Tire in Canada and Sears in the United States. Both retailers had established service networks and existing customer bases. Reportedly, both companies were receptive to the idea of offering an affordable vehicle, with Sears even having a history of selling motorcycles, cars, tyres, batteries and houses.

According to the Globe & Mail, the total projected cost of bringing this car to market could have reached $500 million (approximately $1,278,041,074 CAD today), but unfortunately the project never materialised.

The Venus never transitioned into a production model. The sole prototype is housed in the Musée de l’ingéniosité J. Armand Bombardier in Valcourt, where it serves as a curiosity more than a functional vehicle. It features a working three-cylinder Daihatsu engine and a five-speed manual transmission, but much of the design is purely aesthetic. For instance, the interior includes manual window cranks that are non-functional, as all the windows are fixed in place.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login