In the mid-1960s, Puma sketched out the project for a popular national car, taking advantage of the availability of tools and workers. The big problem, as Gurgel would later discover, was that a car with a fibreglass body could not be produced in large quantities. Buying expensive presses to stamp steel plates would require resources that the young manufacturer did not have.

Nevertheless, Jorge Lettry, one of Puma’s employees, returned from a trip to Europe with the news that the manufacturer Reliant was building up to a thousand cars a month (in fibreglass) thanks to a process of “chemical hardening”. The project of a national minicar went back to the drawing board and Miltom Masteguin (technical director of Puma) and Wilson Drauzio Brasiliense coordinated the team that would build the prototype.

In 1971/72, the minicar, now called “Project W”, aroused the interest of a foreign bank to grant a loan to Puma, but the transaction never came to fruition. The reason was that the loan depended on a guarantee from the Central Bank, which was refused on several occasions. As a result, the Mini Puma project was once again shelved. It is important to point out that between 1971 and 1973, negotiations took place between the Italian car manufacturer Fiat and the Union, with the aim of setting up in Brazil the production of small-capacity, low-price cars.

In 1973, the first world oil crisis condemned large, heavy and expensive models and favoured compact, light and economical cars.

In 1974, the Mini Puma prototype was presented to the then President of the Republic (Geisel). Luís Roberto Alves da Costa, who was Puma’s CEO, complained about the lack of government support for the initiative to build a national mini-car, which would be perfect for the chaotic traffic in the cities and would help to save foreign exchange for the import of expensive and rare oil. The President of the Republic was presented with a friendly prototype with a yellow body and 4 seats.

The Mini Puma was almost a minivan with a steeply raked windscreen and a large glass area. The rear window acted as a third door. The headlights were round, while the taillights were small and square. The small engine was cooled by small rectangles hollowed out at the bottom of the panel where the headlights were mounted. The door handles were rather small.

The small engine was actually half of an air-cooled VW Boxer engine, and the original 1500cc displacement was halved. In this “unprecedented” 4-stroke two-cylinder engine, the two cylinders were horizontal and cast in aluminium and magnesium alloy. This engine allowed extremely variable crankshaft strokes, so the displacement could vary between 500 and 1000 cc. The prototype used a 760 cc engine, which produced 30 bhp at 4,500 rpm. The carburettor was a 30 mm Solex and the electrical system was already 12 volts.

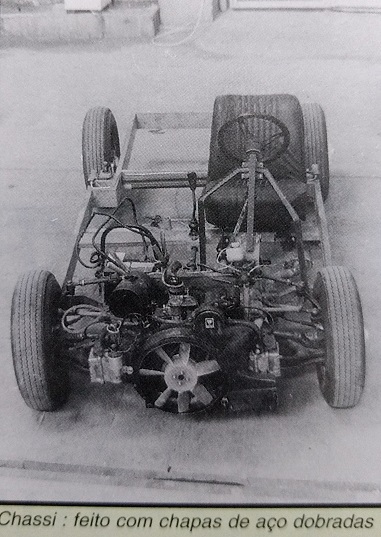

It was also front-wheel drive (but there was some thought to offer a final version with rear-wheel drive) and the front suspension was based on that of the Ford Corcel and had crossbars running from one side to the other at the rear with adjustable attachment points, which could be lifted or lowered easily. The chassis was made of bent steel sheets.

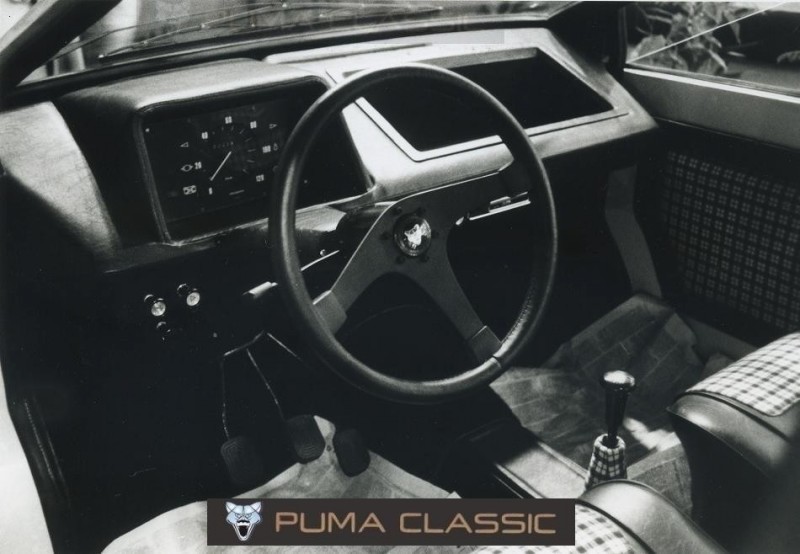

The manual gearbox had 4 gears, the first 3 being quite reduced and the last one very long, which made the car fast in town and loose on the motorway. It had rack and pinion steering and the drum brakes were the same as on the Ford Corcel Standard, with the option of disc brakes on the front wheels. The smooth magnesium wheels had 5-inch rims (and would be optional, as the model would come with steel wheels and the same 5-inch rims as standard).

The body was made of injected plastic. With 2+2 seating (two adults and two children), the prototype had high seats upholstered in black and yellow fabric, but in the final version they were replaced by simpler, lighter and cheaper Percintas-type seats – a solution that did not sacrifice comfort and had already been tried on the popular Willys Teimoso (1965/66).

Despite the small dimensions of the body (2.66 m long, 1.48 m wide and 1.37 m high, with a measly 1.75 m wheelbase) the interior felt spacious and well lit.

Weighing only 500 kg (260 kg less than a Renault Gordini with an 850cc engine and 40 bhp), the Mini Puma promised a top speed of 100 km/h and a fuel consumption of up to 20 km/l of petrol, which was its main selling point in the face of the oil crisis that was to last for many years to come. The tank had a capacity of 30 litres, which gave it great autonomy.

The car was to be built in a factory on a 300,000 m2 site in Franco da Rocha (25 km from São Paulo), but this was never to be. In 1980, Puma suffered a serious blow to its financial health. Around 200 units of the Puma sports car were exported to the United States, but the entire batch was rejected. The reason given was that the cars sent “did not meet the minimum American safety specifications and were different from those sent for preliminary testing”.

A severe flood in the city of São Paulo, in the region where the Puma factory was located, and then a fire caused serious and irreparable damage. Production fell from 3,042 cars (built in 1980) to 471 in 1982.

In 1982, during the last military government (with General Figueiredo as President of the Republic), Luís Roberto again offered the project to the “authorities”, but this time there was an important difference: the friendly Daihatsu Cuore – a 3.20 m long hatchback, front-wheel drive and a 547 cc twin-cylinder transverse engine. Although the new Mini Puma looked very much like the Cuore, its body would be made of fibreglass instead of stamped steel.

Unfortunately, this last attempt failed and in 1985 Puma filed for bankruptcy and ceased to exist shortly afterwards.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login